Last updated on March 3, 2020

Richard Miles sits in a small, box-like office at the Martin Luther King Jr. Community Center in South Dallas discussing his 1994 interrogation when he looks around and notices something.

“When you haven’t done nothing and you’re arrested, they put the handcuffs on you, read you your Miranda rights and then you end up downtown. And it’s at that point when somebody comes in, into a room,” Richard says as he starts laughing. “Oh my God, something like this one. Man. I just had a flashback.”

The flashback took him back to May 16, 1994.

At 3:15 that morning, a then-19-year-old Richard was walking home when he was arrested 25 minutes after two men were shot in a car outside a Texaco station two miles away near Bachman Lake. One of the men eventually died.

A witness described the shooter as an African American man in a white tank top and dark shorts. It didn’t matter that Richard was wearing a white tank top and blue pants when he was arrested.

He was interrogated, sat in a county jail cell for 17 months and was eventually convicted Aug. 25, 1995. Richard was sentenced to 40 years for murder and 20 years for attempted murder. He ended up spending more than 15 years incarcerated for crimes he didn’t commit.

“You deal with every emotion under the sun. From anger to suicide, to loneliness and depression, I experienced all of that,” Richard says. “But when I was incarcerated, I had an opportunity to dig more spiritually into myself. I always fell into my spiritual foundation, and I think that really secured me in going through this transition.”

To understand the Oak Cliff native’s transition, which included a stop at Eastfield College, starting a nonprofit and a trip to New York as a CNN Hero, you need to understand why his life hit an “endpoint” almost 11 years into his sentence.

A New Mindset

When you speak to Richard, you immediately notice how personable he is. That’s not a new quality, but it is something that he almost lost, even though he was initially optimistic after his arrest.

“I had hope because I believed in the truth. I believed in the system. I knew I hadn’t done anything wrong, and everybody says if you haven’t done anything wrong, then you tell them what happened,” he says. “You got your alibis. I didn’t ask for an attorney. I just gave them where I had been. You don’t think about wanting an attorney when you ain’t did nothing wrong, you know?”

He kept that attitude almost up until his conviction.

“They’re going to come and tell me in a minute that they got the wrong person,” Richard says. “And a year later, now I’m in a courtroom after six days of jury trial and eight hours of deliberation. The jury comes back and says, ‘We find the defendant Richard Ray Miles Jr. guilty of murder and attempted murder.’

“And I sat down, and I remember my lawyer kind of nudging me to stand up. ‘Man, you got to remember to respect the court.’ And in my head, I was like, ‘How or why should you respect an entity that hasn’t respected you?’”

By the time he was 30 years old, 11 years into his prison sentence, he had exhausted his appeals. His writ of habeas corpus had been denied. He was looking at nine more years before he was even eligible for parole.

In short, things were looking bleak.

He was working in the infirmary that year. Every morning, the nurses would come in and say good morning, and every morning, broom in hand, he’d respond with “alright, alright.” One day, one of the nurses finally asked him what that meant.

“You know what? I’ve been locked up 11 years, and I’ve never said, ‘Good morning.’ And so, it was at that point that I realized that I was becoming institutionalized. Not even knowing it, but being adjusted to the norms of being in the institution,” he says. “And she challenged me at that point to either keep saying, ‘alright, alright,’ or challenge myself to say, ‘good morning.’”

The next morning, through gritted teeth, he replied with his own “good morning.”

“I had to think about it. Why am I saying good morning? What’s good about it?” Richard says. “Outside of anything else that may be going on, what’s going on doesn’t impact the morning. The morning is still good, regardless of where I am. So, it is a good morning. Maybe bad conditions, but it’s a good morning.”

Small as that exchange was, it changed his mindset. Richard started to regain his optimism and positivity — a point of awakening, as he calls it. It paid off about two years later.

Finally Free

Richard just casually throws out legal jargon when he speaks about his fight to be free. Actually, it’s jargon to you and me, but to someone who fought as long as he did, those terms are part of his vocabulary forever now.

For instance, in 2007, now 13 years into his sentence, Richard learned the police had withheld information about his case that could have helped him and his defense team during his trial.

“And that’s referred to as Brady violations. So, Brady v Maryland is the failure to disclose exculpatory evidence favorable to the defendant,” he says. “All of that evidence could have and would have altered the decision that the jurors had made had they known the state had this in their hands.”

By that point, Richard had been corresponding with Centurion, an innocence organization based in New Jersey, for more than a decade. Centurion purchased Richard’s transcripts and police records and sent them to him in October 2007.

He read all four volumes of the transcripts but didn’t immediately read the police reports. His parents, William and Thelma, brought the police records four years earlier, and there wasn’t anything of substance in those, so there wasn’t much use in reading them again. At least, that’s what Richard thought.

“So, after I read the transcripts, God said, ‘Man, open up the police reports,’” Richard says. “And the first thing I noticed was what my dad sent me. It was 26 pages. What Centurion got me, it was 85 pages.”

As it turned out, his parents were given sanitized police reports. When Centurion filed a Freedom of Information Act request, they specifically asked for the working documents — hence the 59 extra pages. Those extra pages contained a phone memo from four months before Richard’s trial.

A woman called a Dallas homicide detective and told the detective her boyfriend was beating her up and had also been bragging about killing two people. She also gave details about the case that no one but the police and the killer knew.

“And in the memo, the guy says, ‘I have identified the case on this date that I think this is connected to.’ He even went to the case and connected it,” Richard says. “And nobody ever talked about this, nobody ever turned it in, and they had this way before I went to jury trial.”

From there, Centurion and Richard’s retained counsel (lawyer), Cheryl Wattley, came to visit Richard at Cofield Unit in Tennessee County, Texas, in January 2008. They were blunt about what was ahead: When Centurion takes a case on, it’s usually five to 10 years before anyone is freed.

“And I was like, no man, my case is gonna be way faster,” Richard says.

He walked out of prison as a free man Oct. 12, 2009, less than two years after that conversation.

“People miss the life of prison because we come out of prison. But the fact that they gave me my truth back even before I got out — to me, that was way bigger than getting out,” Richard says. “It was bigger because now, somebody knows that I’m innocent. More than my mom. More than me. They gave me that dignity back outside of being in this hole with everybody they feel like is guilty of some type of crime.”

Now What?

Richard was a free man, but he, then 34, was still considered a convicted felon because he hadn’t been exonerated yet.

That made transitioning back into normal life very difficult. He moved in with his mom and started working at the church his dad, who died six months before Richard got out, started years before.

“Everything that I got wasn’t because of me. It wasn’t even because I’m showing people newspaper clippings. It was because somebody spoke up for me. Somebody stood in the gap. And that put me in the mindset,” Richard says. “There are not a lot of organizations out here that are willing to stand in the gap for somebody who’s been impacted by incarceration.

“And so, housing was a hard thing. Employment. Social skills. The geography of Dallas has changed. When I went to prison, I had just gotten a beeper. And now there are iPhones!”

Another way for Richard to get some much-needed money? Grant money for school. His mom told him he could apply for a grant and get paid to go to school. He’d already earned his associate degree in prison, but he figured this was a good path to go down to start a business, so he enrolled at Eastfield in 2010.

“And my first class was speech with Mr. Courtney Brazile. And he pushed me to get out the box,” Richard says. “And to get up and start talking about my story, and just other different things that kind of appealed to me.”

He eventually had to leave Eastfield for a book tour, but being on campus had a lasting impact on him.

“Coming out of prison and walking on a college campus was so victorious. I’m probably like the oldest person with grey hair and everything,” he says, laughing. “Just to be in that space and to know that, you know what, this job turned me away, but this college accepted me. I can’t work at McDonald’s, but I can go to college.”

Miles of Freedom

Finally, on Feb. 15, 2012, almost two and a half years after Richard was freed, Texas’ highest state court, the Court of Criminal Appeals, found him factually innocent of murder and attempted murder. Richard Ray Miles Jr., almost 16 and a half years to the day he was convicted for murder and attempted murder, was finally exonerated.

“It empowered me to now do the things I always wanted to do once I got out,” he says. “I feel like the only difference with my release and a person who’s actually guilty is I had resources. The person who is actually guilty, they don’t have the resources.”

Richard used some of what he was compensated with for his time in prison to start a nonprofit in 2012 called Miles of Freedom. Miles of Freedom provides holistic services for individuals, families and communities impacted by incarceration.

“You have a lot of systemic issues from incarceration,” Richard says. “So, I wanted to create an organization that at least addresses these three points of entry: the person, the family, the community.”

All of Miles of Freedom’s services are free. The organization’s caseworkers help those who’ve been incarcerated with everything from obtaining identification to finding housing and employment. The organization provides lawn care services and has distributed more than 200,000 pounds of produce since last June. The nonprofit provides shuttle rides — three Saturdays a month — for families to visit their loved ones in any of the five Tennessee County prisons.

All that came from an idea Richard worked on with an older inmate he met in 2004 named Aubrey Jones. Since its inception in 2012, Miles of Freedom has helped more than 1,200 people who have either returned home from prison or been affected by incarceration.

“Certain things you can bring out of prison: the mindset to work and the humility to know when you don’t need to fight back right now,” Richard says. “This is bigger than me. Pick your battles. And that’s what I believe we try to wrap into Miles of Freedom. It’s just that humility that we’ve got to approach servanthood with.”

Balance

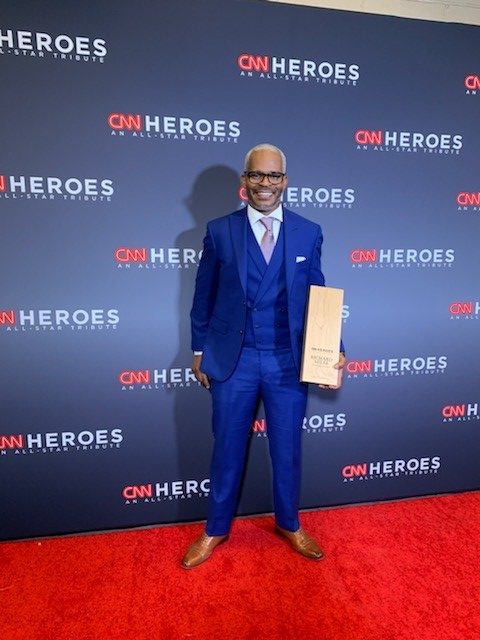

Life took a couple of positive turns for Richard last year. First, Tricia Bridges, a Miles of Freedom board member, nominated Richard to be a CNN Hero. By December, he and his family were flying to New York for the 13th Annual CNN Heroes: An All-Star Tribute, an award show honoring the top 10 honorees. Each honoree received $10,000.

“Man, you know, I had about 30 seconds to give this speech. It was surreal, man. And you know a lot of times, we don’t really know that we’re in the right space in life. But God brings about points of recognition,” Richard says. “You have this opportunity to be this voice for people who may never have this opportunity. What are you going to do with it? Are you going to be selfish with it? Are you going to take it on your own, or are you going to let everybody be a part of this here?

“And that’s what it was for me. How can everybody be included within this 30-second presentation?”

A week prior, his wife, LaToya, gave birth to their second daughter. His oldest is four. It’s almost an understatement to say the last few months have been a whirlwind. So, Richard is only asking for one thing this year.

“Family-wise, man, I just want to enjoy family. My word for 2020 is balance. I’m not asking God for anything more,” he says. “I’m asking for Him to put me in the position that I can balance everything that he has for me to balance.”

He wants to continue to grow Miles of Freedom, which works out of both South Dallas and West Dallas, moving to the legislative side of the fight for families and communities impacted by incarceration. And even though his first chance was unjustly taken away from him, he’s making the most of the second chance he fought so hard to get.

“It’s all good. I tell people at the age of 19, all I had was 60 years and a bunk,” Richard says. “And truth be told, everything I have right now, I know it’s because of God. By man’s account, I’m not supposed to have any of this. By man’s account. So, I accept the good with the bad.”